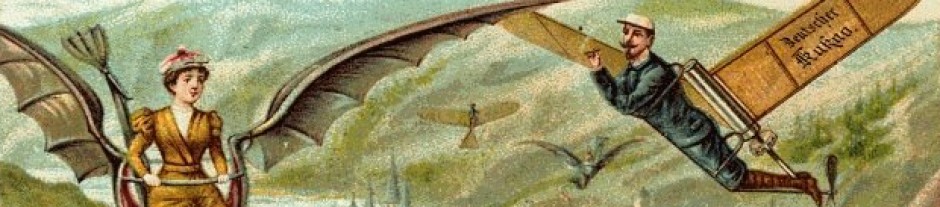

As an alternate history genre, steampunk literature builds its worlds by answering the “what if?” question of science fiction and fantasy; it does so by tweaking nineteenth-century history and literature and engaging with cultural discourses of the day. Steampunk often revises and questions Victorian gender norms, even as it acknowledges the power of those norms. In steampunk fiction, this reconfiguration of nineteenth-century gender roles is deeply enmeshed in the genre’s focus on retrofuturistic technology from which it earns the “steam” part of its name. Moreover, steampunk fiction’s play with and “punking” of the connections between gender and technology can also reveal the work required to maintain the Victorian gender binary, as well as our own.

Keith Thompson, “New Year’s.” Scott Westerfeld, “Bonus Goliath Chapter and Art!,” Scott Westerfeld, December 16, 2011.

Bringing this subversive steampunk approach to gender to young-adult fiction, Scott Westerfeld’s Leviathan trilogy follows the exploits of Deryn Sharpe as she plays a key role in the war between Darwinist Western Europe, whose technology relies on genetic modification of living creatures, and Clanker Germany and Austria-Hungary, whose technology relies on gears and steam engines. Deryn becomes a boy named Dylan Sharpe in order to become a midshipman aboard the Leviathan, a genetically engineered whale zeppelin that is part of England’s Air Service. In the process, she aids and develops feelings for young Prince Aleksandar of Hohenberg, who is trying to stop the world war sparked by the death of his parents.

Reflecting steampunk’s push to occupy the boundaries between binaries, Deryn’s gender cannot be easily classified as feminine or masculine; instead, she occupies what we might call a genderqueer or gender-fluid space in which neither binary label can suffice. This transgressive gender identity makes visible the workings of gender itself in much the same way as a cog-displaying computer plays with the boundary between the analog and the digital, as J. Jack Halberstam argues in Female Masculinity: “female masculinity actually affords us a glimpse of how masculinity is constructed as masculinity. In other words, female masculinities are framed as the rejected scraps of dominant masculinity in order that male masculinity may appear to be the real thing.” In highlighting the breakdown of the man/woman binary, Deryn’s genderqueer identity insists that we re-evaluate our understanding of Victorian gender. We must question whether ideologies of gender can encompass the complexity of any sort of humanity, be it virtual or real, and must therefore question our continued adherence to this dysfunctional binary.

This paper was presented at the 2015 Interdisciplinary Nineteenth-Century Studies Conference at the Georgia Institute of Technology, and the article version of the paper appears in Virtual Victorians: Networks, Connections, Technologies, edited by Veronica Alfano and Andrew Stauffer.